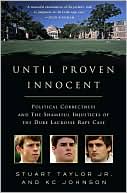

It is far from perfect, quite far. But it is fascinating, it is exceptionally well-researched, it makes an effort to include every known and provable fact about the case, and it certainly leaves no question as to who the real criminals were in the much-publicized case. Read more after the jump.

It is far from perfect, quite far. But it is fascinating, it is exceptionally well-researched, it makes an effort to include every known and provable fact about the case, and it certainly leaves no question as to who the real criminals were in the much-publicized case. Read more after the jump.The case, of course, is the infamous Duke University lacrosse team gang-rape case of 2006. You remember when this was all over the news last spring and summer, when every news show had the faces of these rich, white Duke lacrosse players who had gang-raped and shouted racial slurs at an innocent black single mother who was studying for her degree at a nearby historically black college.

You may or may not remember what actually turned out to be the truth: there was no rape, no crime, the "victim" was lying, the prosecutor knew it, the prosecutor sought to put the three "rapists" in jail to help him win an election even though he knew they were innocent. The prosecutor actually engaged in a conspiracy to cover up exculpatory evidence, failed to actually interview the "victim" for over six months after the crime, and deliberately sought ways to make the lacrosse players seem guilty in the media before he ever made a single charge and despite multiple police interviews and DNA tests that showed they were innocent.

It was one of the worst cases of prosecutorial misconduct in recent memory, certainly the most public (which is sad, because the misconduct only really came out because the accused had good lawyers; poorer folks could easily have been sent to rot in jail to further this DA's political career). Worse, it was rather damning evidence that the mid-1990's spate of extreme political correctness on college campuses nationwide (remember the "water buffalo" incident?) hasn't gone away, as dozens of Duke University professors and much of the administration took a position that the lacrosse players were guilty without ever hearing a single piece of evidence.

This is one of those books that will make you mad. It made me mad. I couldn't read more than a chapter or so at a time before I had to put it down and walk away for a while. The only reason you can get through it at all is that you already know how it ends: you know the guys get off in the end, they're proven innocent. You know Nifong is in trouble. You know that. But it doesn't make reading about the intervening months especially easy.

Of course as I said the book has flaws. It needs a copyedit, badly. Very badly. One of the authors, KC Johnson, a professor at Brooklyn College, is a noted blogger, and the book reads at times like a blog entry, very informal. That's fine, but the copyediting is blog-like, too--which is to say, there hasn't been any. Words repeat, are misspelled, there are words missing, punctuation is missing or inappropriate... it isn't awful, it's not on every page, but it's blatant (I'm not talking about "it's" v "its", I'm talking about leaving the e off the end of the word 'are') and distracting and takes away from the book's power.

Similarly, the authors are both guilty of using the same sort of loaded language against the professors, the DA, and the administration, as they accuse those actors of using against the team members. The lacrosse players were 'trashed' in the media. The assertions of the professors were 'outrageous.' Loaded words like that are thrown around on almost every page, and while as I was reading they fit right in with the narrative, they're a problem. Quite simply, they make the book an easy target as being "biased." It seems like the authors have an agenda (which they clearly do and admit to in the last three chapters), but the story stands on its own merits. You'd be plenty outraged by the facts as they exist without the additional hyperbole. The beast is cooked by the facts; there's no need to continue stabbing it with language.

All is not lost; the authors are not some wild-eyed arch-conservatives. Stuart Taylor, Jr., is a fellow at the non-partisan and centrist Brookings Institute (if you think Brookings is conservative, bear in mind an equal number of people think it's liberal; that's how we know it's centrist), a lawyer, and a legal reporter for a number of media outlets (almost entirely on the left of the political spectrum); KC Johnson is a history professor who's scholarly output focuses on American progressives and their role as dissenters from American foreign policy, a registered Democrat and public supporter of Barack Obama's presidential campaign. These are not raving right-wingers. Johnson was once denied tenure for having the temerity to question whether a panel set up by CUNY to discuss the 9/11 attacks should maybe have at least one person who didn't think American foreign policy was the proximate and only cause of the attack. The very last chapter of the book is clearly Johnson's axe-grinding; two chapters before looks to have been Taylor's work, an attack on the grand-jury process and the inadequacies of the justice system to guarantee defendant's rights and prevent the innocent from being convicted.

It would be easy to write this book off as a right-wing attack on left-wing academia, and no doubt a number of the academics mentioned in its pages (disparagingly, for the most part) have said just that. Unfortunately for that story, the facts don't bear it out. In any other book, chapter 23, a plea for the rights of the accused in criminal cases, would be taken as so much left-wing hand-wringing when we should really be focused on victim's rights. Both authors actually appear to be somewhat to the left on the political spectrum--though to those on the farthest fringes of the left, moderate liberals are often seen as conservative (exactly the same phenomenon occurs on the far right; note the number of conservative politicians labelled "RINO" (Republican In Name Only) by the far fringe).

This is a story that needs to be told. This book was much needed, as a historical work, as an attempt to force the named parties to come to grips with the truth of what they did, as an effort to provide public proof that the three accused men were indeed innocent of any crime and should never have been treated as they were by the police, the press, the DA, and their own university faculty and administration. It is precisely because the book was so needed that it's glaring problems are so bad--an important historical work that seeks (and needs) to be taken seriously should take itself seriously; another two weeks at the editing desk would have cleared up the copy problems, and a two-week rewrite could have neutralized the language. Then we'd have had a book that would have to be taken seriously; this one compares to much to a blog, and that's a shame. The last line of the book states that "it's the facts that matter," and that's true, but in such a political atmosphere as this book and this case play out, style goes a long way to getting people to pay attention to the facts.

It's a good read, a rather ripping yarn, and an important book; but it's not what it needed to be.

No comments:

Post a Comment